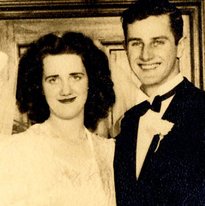

Norma & Jerry Mealey-1947

Norma & Jerry Mealey-1947 I was going to wait until June 30th, the 20th anniversary of my Mother’s death, before I republished this column from 1994, the year after Mom died. It was a lonely time then, trying to figure out how to live with the fact my parents were gone and gone way too soon. Now, 20 years later, I am watching my peers deal with the heart-wrenching ordeal of caretaking their aging, dementing and ailing parents; becoming parents to their own parents. Some of them are still parenting their own children. No matter how old we are, we become an orphan when our parents leave us and it is a transition we must face.

This column was first published in September 1994 when I entered a “Replace the Columnist For A Day” contest in my local newspaper, The Davis Enterprise -- a brilliant way for our beloved columnist, Bob Dunning to get his summer vacation! Bob, along with Erma Bombeck and Marjorie Holmes have been my secret writing mentors for years. Thanks for giving me the nudge, Bob!

Too Young To Be An Orphan

I’ve heard many times that the worst tragedy anyone can suffer is losing a child. Not having gone through this myself, I struggle to completely understand how it really feels. I have compassion and sympathy for grief-stricken parents, but still I cannot truly comprehend the depth of their pain.

So it is, I imagine, for my friends, when I talk about the death of my parents. Few of my friends have suffered this loss, making me a pioneer among my peers. They listen and sympathize, but can’t really know.

My father died six years ago and my mom just a year ago. Daddy and Mommy never told me how hard it would be to go on without them. They never warned me of these new feelings of mine: abandonment, loneliness, and helplessness. They protected me, I guess.

I knew something about bereavement since I was there when my parents lost their parents. I remember hearing how they went to the cemetery together, held each other and wept. I listened to their indecision about money and retirement matters as they learned to make these decisions without the advice of their elders. I saw the sadness on their faces as they remembered their parents on the anniversary of their births, as well as their deaths. I felt the emptiness of the room at Christmas time and felt the chill as someone sat in Grandma’s chair. Our family still ate off Grandma’s china, but now it was stored in our hutch, not hers.

I remember clearly how my father and I confronted the death, together, when his mother died. Granny was 83 and I was 22, but we were close friends. Granny had cancer and I had just taken her back to New York to visit my cousin whom she had raised from a toddler. I knew this could very well be the last act of friendship I performed for her. She had never flown before and sat on the 747 with eyes sparkling, so characteristic of her adventuresome and sometimes ornery spirit.

Granny talked of many things on that five-hour flight; mostly about the changes in the world since her birth in 1893. I listened to her stories intently, knowing I would pass them down to my own children.

During our second week in New York, Granny died. I was alone with my cousin in a hospital 3,000 miles from home. Suddenly, I was making tremendous decisions about Granny’s life and death as she was rushed into surgery. I tried to keep her spirits up as we awaited the arrival of my father and aunt who were flying in from Oregon. Though they came immediately, it didn’t seem fast enough.

I had expected Granny to live. I didn’t know she was waiting for her children to arrive before she left this earth. When Dad arrived, I no longer had to be the adult. Daddy was here. He could be the boss. I never knew that when he arrived he became the child again, full of fear and anxiety.

We all left to go to my cousin’s home to plan a schedule of shifts with Granny. But, five minutes after we arrived there, the hospital called. Granny had died. Dad was strong, but I collapsed. The only consolation was that I still had my parents. I was still the little girl, and we could all go on. In my own comfort, I did not understand Daddy’s feelings – for he had just become an orphan.

Now, 20 years later, I’m the orphan. At times that fact overwhelms me. Daddy and Mommy never told me how empty the mailbox would seem on my birthday, or anniversary, or Christmas when it no longer held a card from them. They never told me how hard it would be to control the urge to call home during my worst times. They never told me how shrill the ring of the phone would sound when I knew as I answered; it would never again be them.

They never explained how hard it would be to go back to my family reunions in Oregon and see their eyes in the faces of families from a brother or sister or cousin. But even if they had told me, the comprehension would have been slight—like a childless woman listening to another woman’s childbirth story.

I have matured as an orphan. I have newfound confidence. I’ve inherited a parental and adult-like strength I never knew I had. Now I can straightforwardly tackle what previously seemed impossible, thanks to skills I learned from my parents. I am an elder of the family now, and my kids look up to me with confidence.

But I still waiver. I still call out for Mommy in times of pain. I still ask Dad which wrench to choose. I still start to dash to the phone to call them when I’m suddenly stopped by the reality of their deaths. I still want to share the joys of their grandchildren with them. I still need those comforting arms around me when nothing else will do.

At 42, I am still too young to be an orphan.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed